Last Monday, I wrote about large corporations needing to adapt to the changing times to continue attracting the most talented business graduates. Yet, I wasn’t espousing an all out war for talent. On the contrary, there are many ways for corporates and startups to collaborate in this ongoing digital revolution. Just two days later, Germany immediately showed us one model to emulate. Daimler AG, the German automotive giant that owns the Mercedes-Benz brand, led a $30M investment in German start-up Volocopter, which is developing an electric autonomous flying taxi. This model — called Corporate Venture Capital — is one that Southeast Asia vitally needs to further expedite the growth of its startup and venture capital ecosystem.

In startup circles, venture capital is the sought after funding that helps founders bring their ideas to reality. As the subset of investors that focuses on early-stage companies with high-growth prospects, venture capital funds (VCs) can be dissected even further into the stages in which they invest: seed, early, growth, and late. A lesser known category of investor in startups is known as Corporate Venture Capital (CVC). These are corporations that invest in external startup companies directly or through their own fund.

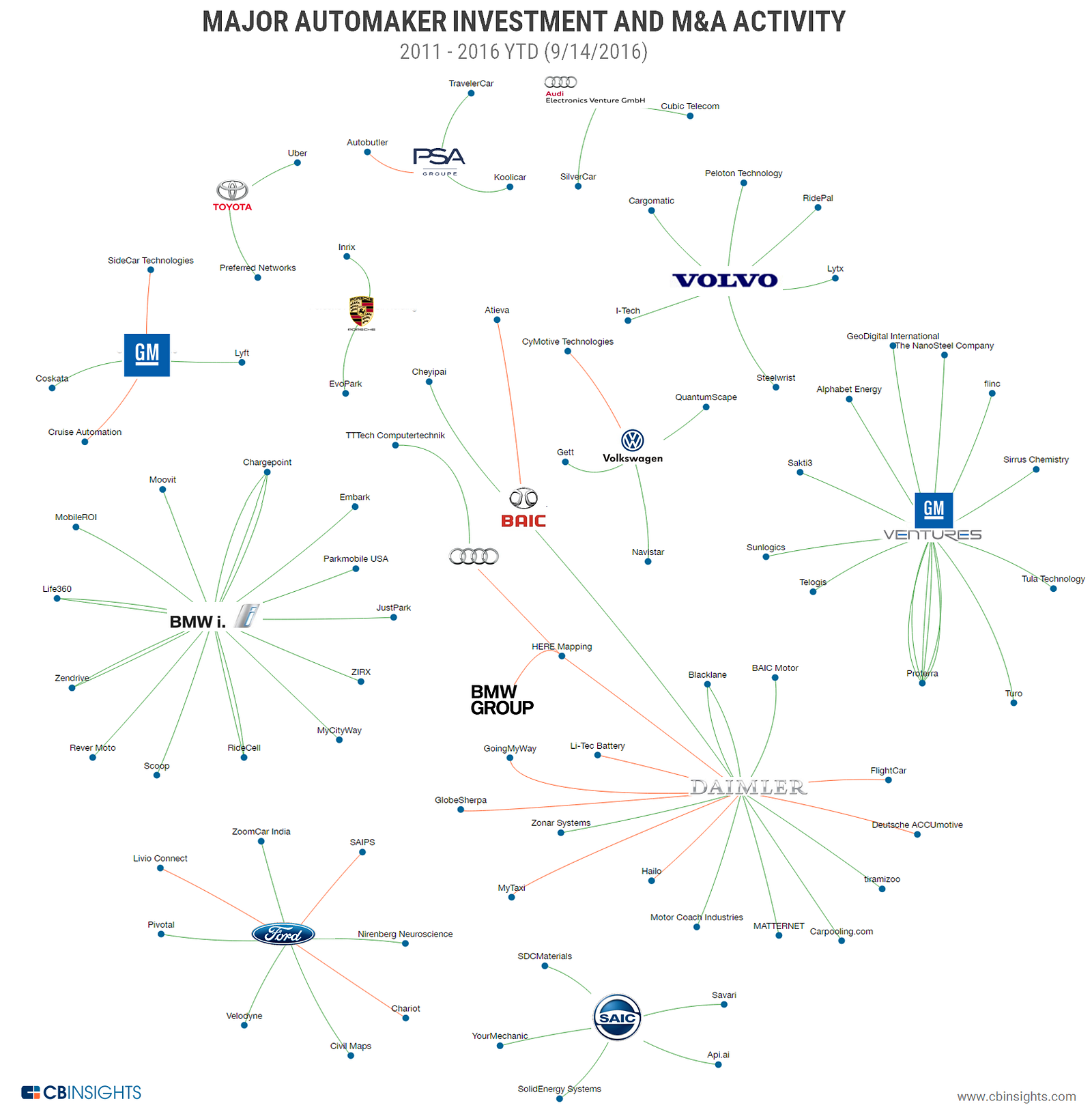

In 2013, Daimler entered a partnership with accelerator Startupbootcamp that allowed the automotive multinational to evaluate 1000 startups across 18 countries. Since then, Daimler has shortlisted their top 40 and ramped up its collaboration with startups significantly. In a September 2016 report by CB Insights, Daimler is shown to have invested in 6 startups in the preceding year alone. These investments are mostly in related industries including a chauffeur booking portal (Blacklane), fleet management systems (Zonar), e-commerce delivery (Tiramizoo), and drones (Matternet). Two other German giants, BMW and Volkswagen (including affiliate brands Porsche and Audi), have invested heavily in startups over the last 5 years.

Germans are also happy to take the Passenger Seat

As depicted by this German model of innovation, taking the driver’s seat is not always the best strategy. In particular, these German automotive companies, have deemed it suitable to take the passenger seat and let startups take the lead. This collaborative strategy allows large corporates to learn about and benefit from new technologies without immediately veering away from their favored lanes. By investing in startups and taking board seats, corporates can work with and guide talented founders.

Best of all, the option to eventually take over the wheel always exists as depicted by Daimler’s acquisition of FlightCar in July 2016. This takeover allowed Daimler to incorporate the technology platform of the airport parking solution provider into its innovation lab. More importantly, some of FlightCar’s 90 employees, including its 21-year old co-founder and CEO, decided to join the German conglomerate. Apart from FlightCar, Daimler has also acquired at least 8 more startups in the past 5 years allowing them to improve their technology while simultaneously building their talent pools.

Backseat Driving and other permutations

It goes without saying that investing in startups is not a strategy that can be easily implemented by all corporations. VC is a highly specialized field and corporations would need one or more full time investment professionals to ensure the success of such an endeavor. Fortunately, there are numerous permutations of the CVC model, which have been enumerated in great detail in a July 2017 Orrick report.

As noted by Orrick, another option that requires much less capital (but possibly more executive time) is the incubator/accelerator model. This model also entails an equity investment but at a much earlier stage of a startup’s development. Most incubators and accelerators invest small amounts of capital at seed stage usually with only an idea and always with minimal proof of concept. This strategy requires a portfolio approach where a wide net is cast to increase exposure to potential winners. In a January 2016 report by Future Asia Ventures, they noted that there were already 23 corporate accelerators in Asia. Among these are the Tune Labs program of AirAsia, the Ideaspace program of Smart Communications and the original Kickstart program of Globe Telecom.

For corporations that are not yet ready to take the step to invest in startups, a much less capital intensive option is a Startup Program. There are Outside-In Programs, which offer startups an opportunity to work with corporate executives with a view of eventually becoming a supplier to the corporation. There also are Inside-Out Programs, where large corporations share their technology to startups to help them develop and commercialize new businesses. For both models, we can look to Germany again for some great examples including “Technology to Business” by Siemens and the “Digital Accelerator” by Allianz for Outside-In and “Startup Platform” by Sutor Bank for Inside-Out. In a sense, these models may be seen as backseat driving where corporations have no capital infusion but continue to share resources and provide insight.

Clearly, there are many options for corporates to concurrently monitor disruptive technology and talented recruits. In Southeast Asia, CVCs and their various implementations will go a long way in helping the startup ecosystem grow organically. In turn, the more robust a startup hub is, the more international talent it attracts. As mentioned in my overview of the European and Southeast Asian VC ecosystems, the first wave of regional winners have emerged. It is time for more corporates to find seats beside talented founders.

Originally appeared on Miguel Encarnacion’s Medium post.